It’s well known that there is a robust association between work and health. For example, some studies have described how the chronic stress associated with upcoming deadlines at work was associated with a six-fold increase in the incidence of heart attacks 1.

Read on to discover some of the surprising links between work stress, our sense of control, our ability to adapt to challenges, what this means for our health and how we can use this knowledge to improve both our wellbeing and our performance.

The difference between feeling stressed or stressed out

While many studies have focused on the relationship between work stress and outcomes such as burnout and cardiovascular health, relatively few have investigated the links between work stress and hard medical outcomes such as specific diseases and, ultimately, death. It’s not a cheery subject, but it’s an important one, particularly as rates of work-related stress continue to rise.

Allostasis is a term used to describe the process of maintaining homeostasis (steady internal, physical, and chemical conditions) through adaptive changes to our internal environment, i.e. changes which make us better suited to meet the demands which we are facing 2.

The allostatic load model provides a helpful framework to consider stress in its various forms; both as excitement and challenge (“good stress/stressed”); as well as an undesirable state of chronic fatigue, worry, frustration and inability to cope (“bad stress/stressed out”)3. The allostatic load model also accounts for the fact that our social environment has a cumulative impact on physical and mental health via the two-way communication between our brain and the body, mediated by the endocrine (hormonal), immune and autonomic nervous systems.

Depending on the circumstances, these systems can exhibit a healthy and adaptive response to stress, or an unhealthy, maladaptive response, either in the form of over activity or under-activity. For example, glucocorticoids and catecholamines are the primary hormones associated with the stress response. These hormones have both protective and damaging effects on the body. In the short term, they are essential for healthy adaptation to stress and homeostasis. Still, over longer time intervals, they are associated with a cost (allostatic load)4 leading to deterioration in physiological and psychological systems, and subsequently many of the diseases we see in modern life.

Types of allostatic load

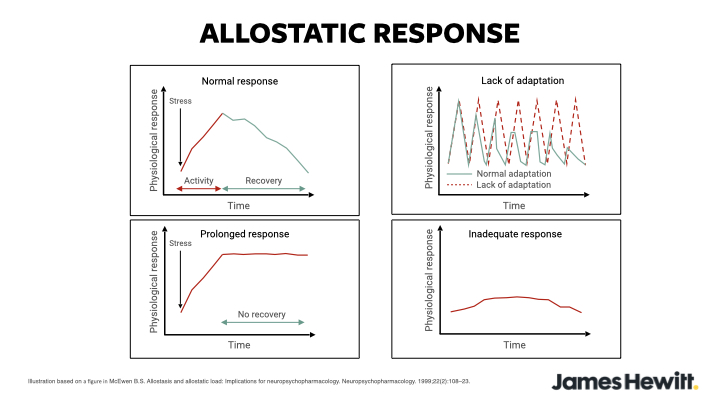

Hormonal responses illustrate several patterns which describe different types of allostatic load as healthy adaptation, over-activity or under-activity.

- Normal allostatic response: a stressor initiates a response which is sustained for an appropriate amount of time, before switching off.

- Repeated ‘hits’ from multiple novel stressors results in a failure to adapt.

- A prolonged response, due to switching off being delayed, results in a failure to adapt.

- An inadequate response that leads to hyperactivity of other hormones (such as cytokines), which are usually regulated by glucocorticoids.

Job demands and control

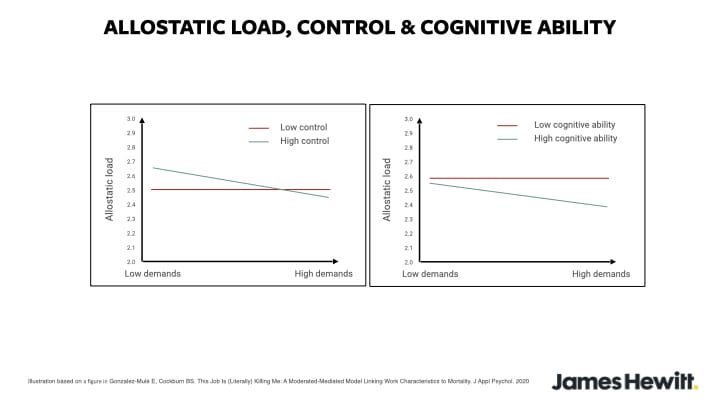

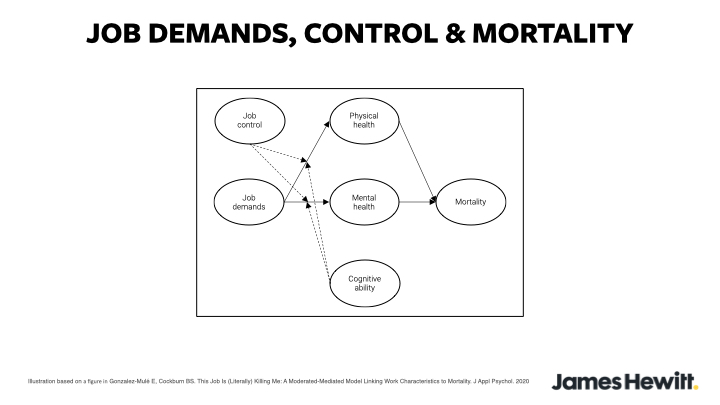

A recent study set out to investigate the relationship between work characteristics and mortality, using a combination of mental health and medical data, from 3,148 people, gathered over 20 years. In a paper titled “This Job Is (Literally) Killing Me”5 the authors, Erik Gonzalez-Mulé and Bethany Cockburn, applied the allostatic load model, combined with measures of mental health. The results reveal some of the factors which predict how dangerous a stressful job may be for health and wellbeing.

In particular, the data indicates that when job demands are high, but the worker’s job control and cognitive ability is low, the allostatic load and risk of depression increases. In turn, this increases mortality (risk of dying from anything). In contrast, if workers have a higher sense of control, and greater cognitive ability, when job demands increase, the allostatic load decreases (indicating better physical health), and the change in probability for depression is small. In turn, this decreases mortality.

Control is critical for healthy adaptation

The results of the study highlight several crucial points for both employers and employees. Providing workers:

- Feel that they have the ability to influence what happens their work environment, particularly concerning matters that are relevant to their goals, and

- Have sufficient cognitive abilities (i.e. their ability to learn and solve problems is appropriately matched with their work tasks)

When work demands increase, they should healthily adapt to the challenges and demands they face. However, if workers experience a lack of control and a mismatch between their cognitive abilities and their tasks, when job demands increase, physical and mental health are more likely to decrease, and mortality may increase.

What can we do?

The results of several studies indicate that different experiences of job demands and job control are likely to represent the basis for many health and performance outcomes, so it makes sense to explore how we can positively influence these factors.

Job control

Try to find a moment to take a step back and ask yourself the following questions about your work:

a. What is happening now? Has your situation changed? Do you feel able to influence what is happening? How well do the demands of your role fit with your ability to meet these demands?

b. What should happen in the future? How could your situation be improved? What could be done differently? What needs to be corrected?

c. How can you bridge the gap between what is happening now and what should happen? Is there something that you can do today to bridge this gap? Is there someone you need to speak with, to explain the challenges and opportunities you see? This blog about shifting ‘why to how’, may provide some useful ideas.

Job demands

Begin by considering the demands that you place on yourself and others, and try to make sure that they are realistic and achievable. This “5-tips to improve your focus” blog includes some practical ideas to help you think clearly about the demands of your tasks, including steps that you can take to work smarter, not harder.

Physical health

A high sense of job control seems to have a positive effect on physical and mental health, but we can also influence our physical health directly. Particularly when job demands are high, and routines are disrupted, it can feel challenging to fit exercise into our schedule. But even short workouts (think 2-5 minutes) can make a significant difference. View ‘could a two minute workout really improve your fitness‘.

Cognitive ability

Many people are looking for ways to improve their cognitive performance and mental sharpness. Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation. I wrote a short e-book, featuring practical, evidence-based insights to maintain and improve your cognitive performance.

Mental health

Learning to manage and adapt to stress is critical for health and performance. As a starting point, you can discover more information about how the body and brain respond to stress, including some stress management tools and techniques.

While it’s clear that there is a powerful association between work stress and some severe negative health outcomes, there are lots of practical, simple steps that we can take to mitigate this risk, to improve both our wellbeing and performance significantly. Whether you are an employer, or an employee, I encourage you to pick one idea, and try to put it into action this week.

References

- Johansen C, Feychting M, Møller M, Arnsbo P, Ahlbom A, Olsen JH. Risk of severe cardiac arrhythmia in male utility workers: A nationwide Danish cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(9):857–61.

- de Kloet ER. Corticosteroid Receptor Balance Hypothesis: Implications for Stress-Adaptation. In:

- Fink G, editor. Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior: Handbook of Stress Series. 1st ed. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2016. p. 21–31.

- McEwen BS. Stressed or stressed out: What is the difference? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30(5):315–8.

McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: Implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;22(2):108–23. - Gonzalez-Mulé E, Cockburn BS. This Job Is (Literally) Killing Me: A Moderated-Mediated Model Linking Work Characteristics to Mortality. J Appl Psychol. 2020;