Many of us aspire to lead a ‘balanced life’, but do you know anyone who has achieved it? Personally, I’ve given up. I think it may be time to abandon the premises of ‘balance’. I don’t profess to have all the answers, but I’m going to share the framework that I use to help manage the many competing priorities in my life and work, while I try to avoid burning out in the process. I hope you find it useful!

Decisive moments

I spent several years as a full-time racing cyclist, as well as working with many riders, as a coach. For the majority of a bike race, riders aim to maintain an intensity of effort within reasonably narrow parameters; not too hard, but not too easy, either. Too easy and the rider will not be able to hold their position in the peloton. Too hard and they may not be able to recover sufficiently for later efforts. A 5-hour race can be won, or lost, based on small decisions about whether to push into the red, or whether to hold back. Bike races are characterised by decisive moments, requiring riders to consider effort in the macro and the micro. Over-emphasising either ends of the spectrum can be unhelpful.

The problem with balance

And here lies my fundamental problem with balance. I understand why we seek balance; we want to manage the multiple competing priorities in our lives, to perform well and maintain our wellbeing. However, I’m not convinced that the pursuit of balance is useful or realistic. It can narrow our frame of reference, focus on the short-term, and generate unrealistic expectations. The pursuit of balance could even end up contributing to burnout. If every decision is measured against the idealised goal of striking the perfect balance between our priorities, we’re doomed to fail, much of the time.

Balance does not leave enough space for risk and compromise. In a bike race, and in life, decisive moments are fraught with uncertainty. We are unlikely to have all of the information we need. Is the upcoming meeting important enough to trade time-off in the evening to continue preparing for it? Should you stay in bed in the morning, or go to the gym? If our frame of reference for each decision is an idealised notion of balance, it can be paralysing.

This is why I advocate ‘zooming out’. Rather than pixelating your perspective and agonising over what you think is the balanced choice in any given moment, change your frame of reference to encompass a broader view.

Set your parameters

People often ask me what metrics I track. I’ve gone through periods of using multiple wearable devices simultaneously, to favouring abandoning them all, in favour of a mechanical watch. However, I’ve consistently tracked three variables each day, based on three simple questions, to help me manage decisions in the micro and the macro.

Each day I rate my response to the following questions, where 1 is the worst, and 10 is the best:

- Cognitive: How mentally sharp do you feel today?

- Physical: How physically fit and healthy do you feel today?

- Purpose: How aligned with your sense of purpose do you feel today?

I answer the questions each morning. I don’t give too much thought to my specific response each day. I answer based on my ‘gut feeling’, but I keep track of my responses on a simple spreadsheet.

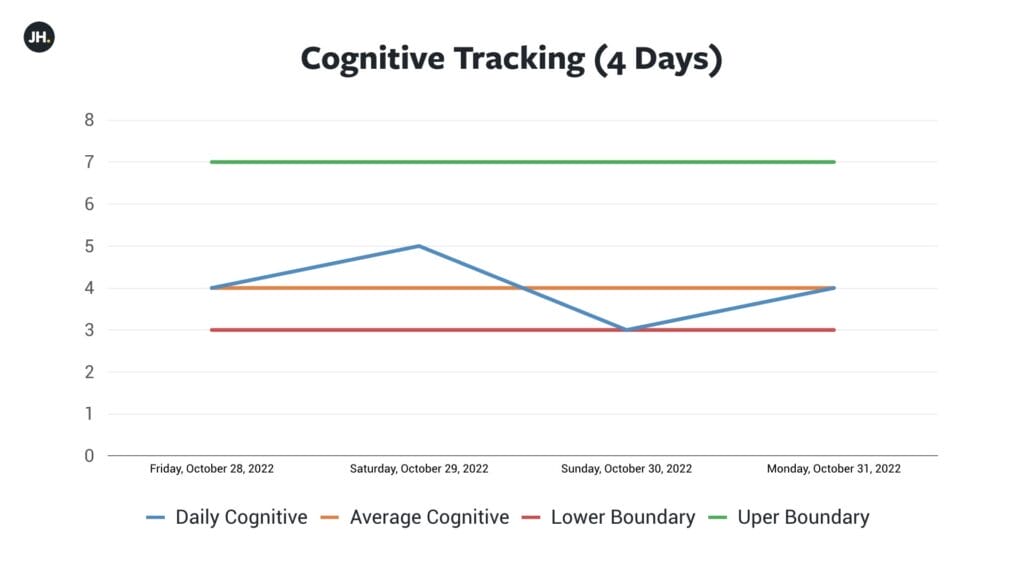

I’ve shared an example chart below, based on my cognitive scores over four days, recorded last year.

- The blue line indicates my cognitive score each day.

- The orange line indicates the average score over four days.

- The red line indicates what I consider to be the ‘low-boundary’ for my scores. Ideally, I don’t want anything to drop below a three.

- The green line indicates the ‘upper-boundary for my scores. Obviously, it would be great to be a ‘10’ all of the time, but during the period in question, I decided that a 7 indicated I was doing pretty well.

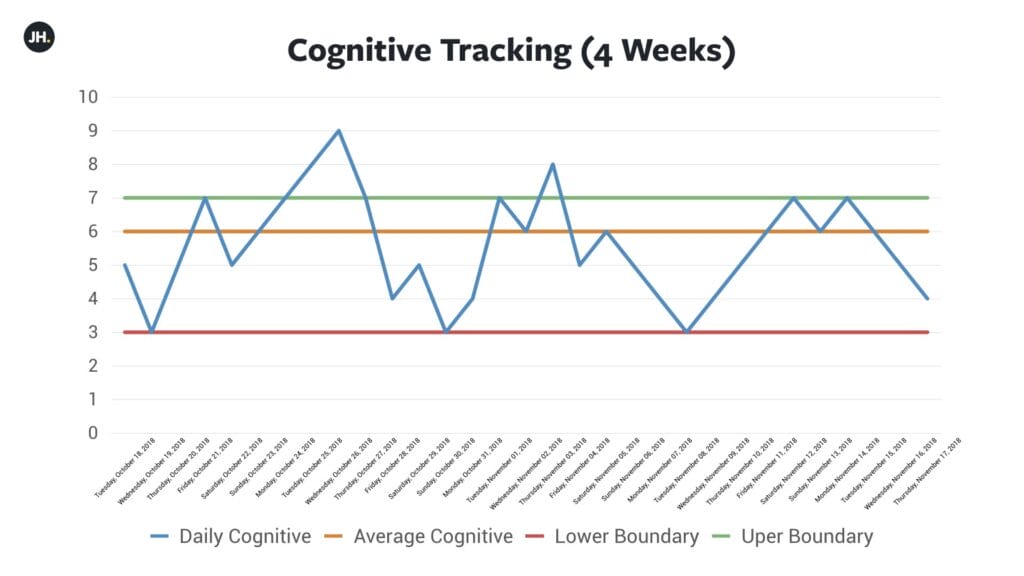

During this time, I was skipping through time zones to deliver several keynotes. I also caught up with a friend from university, resulting in enjoyable, cognitively stimulating conversation, but physiologically costly alcohol consumption. If you had spoken to me during this time, I would have probably said that my life did not feel very balanced. I hadn’t exercised enough, I drank too much, and I slept poorly, but I didn’t beat myself up. I zoomed-out and looked at the average over four weeks. Even though this four-week block was demanding, on average my cognitive score was quite high, almost at the upper boundary.

The most important question

There is one more question I ask myself regularly, and I think it is even more important than the three daily questions.

I don’t believe that life and work are a zero-sum game, but trade-offs are inevitable. I decided that it was worth compromising my sleep to spend some time enjoying a few drinks with a friend. I also decided that it was worth flying around to speak at the events, despite disrupting my circadian rhythm. In contrast, during this time, when I did manage to get to go to bed early, I did not allow Netflix ‘auto-play’ to steal another 45 minutes of sleep with an extra episode of whatever series I was working my way through, at the time.

The most important question I ask myself is “Is it worth it?”

Progress, not perfection

A living organism is never balanced. We exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. We continually adjust, within a set of constraints, or boundaries. I encourage you to consider what boundaries are acceptable for you. Which daily measures are most meaningful? Try to identify your decisive moments; when it might be a time to push into the red, or rest and recover, but accept that you will never have all the information. Make a decision with the information you have, then zoom out and reflect on how you are doing. Aim for progress, not perfection.