Despite the burgeoning mental health app market and their popularity in workplace wellbeing strategies, research shows mixed results regarding their effectiveness. Some studies indicate they are beneficial in managing symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression when compared to no intervention. However, their efficacy appears to lessen when compared to more robust treatments such as face-to-face therapy. More research is required to understand when and how to best use these digital tools. While they shouldn’t replace established treatments, they may be worth considering as supplementary interventions.

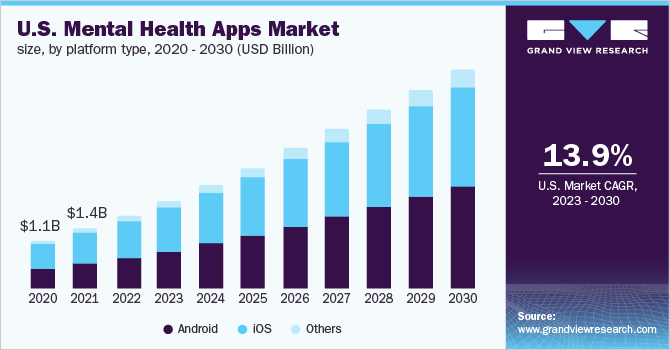

The global market for mental health apps was valued at USD 5.2 billion in 2022 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.9% from 2023 to 2030. Two years ago, it was estimated that there were more than 20,000 mental health apps available. Incredibly, just two apps—Headspace and Calm—account for 90% of active users. If you were to base your conclusions on the headlines, you might assume that there is a massive weight of evidence describing the effectiveness of these app-based interventions. Not so fast…

Many companies I’ve worked with have trialled or continue to use mental health apps as part of their workplace wellbeing offer. Often, the apps are introduced after a senior management team member has had a positive experience or after someone was approached directly by a company to run a pilot. However, few companies put in place any robust method of measuring the efficacy of these interventions beyond reporting the number of ‘activated accounts’ on the app. Consequently, I’ve often been asked what academic research has to say about the effectiveness of mental health apps once they are already being used.

What does the evidence say about mental health apps?

Since last year, one of my go-to studies to answer this question has been a systematic review of 14 meta-analyses (a method that combines the results of multiple scientific studies), which represented 145 randomised controlled trials and 47,940 participants. The primary studies included tested a variety of interventions, some of which are widely used commercial products (including Headspace), while others were academic interventions designed in collaboration with researchers.

Overall, the findings were mixed. While the analysis didn’t find strong evidence that the mobile-app interventions work across the board, they did find some promising results. For example, eight of the 34 results which were examined provided a good indication that smartphone interventions were better than inactive controls (i.e. doing nothing) in terms of positive effects on psychological symptoms such as anxiety, depression, stress and quality of life. Also, apps for specific use cases, such as text messages to help people quit smoking, demonstrated efficacy.

How do these apps compare to most rigorous interventions?

The effectiveness of apps was less clear when the interventions were compared to more robust treatments. The more rigorous the non-smartphone-based comparison treatment, such as face-to-face therapeutic treatment, for example, the less effective the mobile intervention seemed. It’s worth noting that no adverse effects from the mobile interventions were reported. Also, there are limitations to the review. There may be evidence that smartphone interventions are effective, which was not discovered by the researchers or perhaps has yet to be published. Also, the review didn’t consider publication bias, so it might have missed some studies with less dramatic but still important findings.

The researchers concluded that while these tools might have some potential, more research is needed to know when and how to use them effectively. In conclusion, my view is that if the apps are not taking the place of better-established interventions or treatments, they may be worth giving a go. If you’re interested in reading it, you can find the review here.

Reference

Goldberg SB, Lam SU, Simonsson O, Torous J, Sun S. Mobile phone-based interventions for mental health: A systematic meta-review of 14 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(1):e0000002